Something I want to work on with my final draft is the conclusion and a deeper dive into my passive voice.

Introduction

Cosmetics have been a constant throughout history as a way to change an appearance, whether male or female, to impress society. Production of cosmetics improves regularly, including determining what materials should be used for certain products, or the application of cosmetics to one’s face. In ancient China, materials for cosmetics were scarce and most likely came from very toxic materials. Cosmetics were more commonly used by women in ancient China. There have been scientific studies providing evidence of the cosmetic materials used by the Chinese. This blog post will discuss the cosmetics used by women in ancient China, as well as the unearthed evidence recently found of ancient Chinese cosmetics.

Female Cosmetics

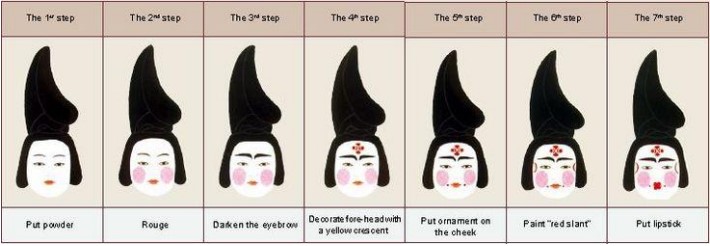

Throughout time periods in China there has been a development of cosmetics. Like today, makeup is very popular among women because it pleased the eyes of men but also was favorable to see on women. One of the most popular cosmetics used was a golden yellow tint to a woman’s forehead. Face readers asserted that a yellow aura around the forehead was extremely auspicious.1 This yellow paint contained lead oxide or massicot, which was less popular than that of orpiment.2 Women applied orpiment directly to the skin. This is a very toxic substance containing arsenic sulfide, and like lead paint it is harmful when left on too long. These yellow foreheads were most popular during the T’ang Dynasty (618-907 BCE) but this favorable style has dated back to the sixth century. Ceruse was another popular cosmetic used to give a woman’s face a white tint. Ceruse is a white lead, which is also harmful to the skin when left on too long. This face powder can also be applied to the breast under the rule of the T’ang emperors.3 Ceruse was popular among women of the upper class, as well as Empress Tu-ku of the Sui Dynasty. Women also colored ceruse to give more color to their face, such as making a rouge color to apply to the cheeks. This powder was favored by court ladies of the Wei Dynasty and became popular in China as well as Japan. Ceruse was given the nickname “flower of lead” as well as “blended lead” for the face.

While ceruse and orpiment were the most popular cosmetics, vermillion and mercury tinted the color of women’s lips. Vermillion is a red pigment made from mercury sulfide, which is also known as cinnabar.4 All of the cosmetics used by women were toxic to their skin when left on for long periods of time without knowing the damaging effects to their skin. Other products used by women included murex purple, a cosmetic created from a murex snail, which women used to lengthen their eyebrows; and Oak galls and bhallataka, two dyes used to color hair darker. 5

If women wanted to take a more natural route to their cosmetics, they could use bat brains in order to remove blackheads. They could also ingest or apply animal or vegetable matter to improve the look of their skin.6 There were also face creams made of apricot pits mixed with sesame seeds that women would use to “make the face glow” and would be applied three times on a daily basis. Cosmetics were also of very high value during the Tang Dynasty because a pleasant appearance was pleasing to women as well as the public eye. It is interesting today to read about these different cosmetics used by women in comparison to today’s known products that cause less harm to the skin. As said by many women, “Beauty is pain”.

Discovery of Freshwater Pearls used as a Cosmetic

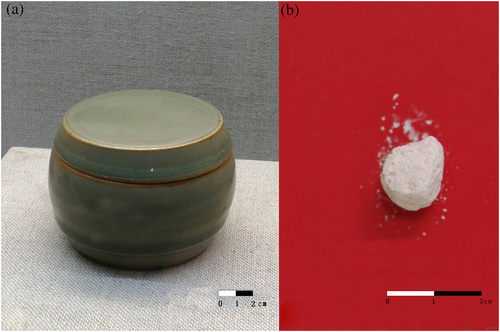

Although there is a lot of historical evidence of cosmetics in ancient China, there is little to no scientific evidence or resources provided for these cosmetics to support the historical facts. However, there has been an improvement in this scientific evidence in the twenty-first century. In 2010, the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology conducted research and extracted evidence of freshwater pearls as a cosmetic during the Northern Song Dynasty. The researchers found the freshwater pearl powder in a large tomb of noblemen, who were from the Lv Family. The tombs are located in Lantain, a Shaanxi Province in China and home to a family of high rank, who were most likely politicians of some sort because of their influence in Chinese history. This set of family tombs are the most complete set of family tombs of high ranking, according to the article.7 The Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology unearthed all kinds of important artifacts such as pottery porcelain, stone, bronze, iron, gold, and many more. The most important of these artifacts is a porcelain box containing a white powder inside. The drum shaped Yaozhou porcelain box was used as preservation of female cosmetic supplies.8

This porcelain box belongs to the tomb occupant, a 22 year old girl named Quin Rong Lv, the granddaughter of a high ranking politician in the Lv family. In order to determine the chemicals within the white powder, scientists tested for two types of white faced makeup material, lead-based white compounds and white compounds based on natural minerals. Lead-based white compounds include chemicals such as phosgenite(a lead chlorocarbonate), cerussite (a lead carbonate mineral), galena (a lead sulfide mineral), and laurionite (a lead halide material), which all toxic chemicals to the skin.9 White compounds based on natural minerals included talc (magnesium silicate), calcite (calcium carbonate mineral), kaolinite clay (aluminum silicate), and barite (barium sulfate mineral).10 Many different experiments were conducted on the white powder including X-ray diffraction, Scanning electron microscopy, Differential scanning calorimetry-thermogravimetry (DSC-TG), Fourier transform infrared (FT–IR) microscopy, inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP–AES).11 These experiments helped to determine the white powder contents to be pearl aragonite, found in freshwater pearls, as well as evidence of processing these pearls using stone grinding tools. This study provided the first form of evidence of freshwater pearls as a form of makeup used by women of ancient China. This white powder was made from natural minerals, which was beneficial for the people using this powder during this time period. They were able to understand the cosmetic effects of pearls in order to use them as skincare products.

Scientific Discovery of 2700 Year Old Face Cream

Furthering this discovery of ancient China cosmetics, a 2700-year old face cream from the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BCE) was unearthed in 2019 by a group of archaeologists, further improving scientific knowledge of ancient China cosmetics. The location of the face cream was the Liujiawa site, located on the southern edge of the Loess Plateau in northern China, was the late capital of the ancient Rui state in the early to mid-Spring and Autumn Period.12

The face cream was most likely used by an aristocratic male, most likely a nobleman of the Rui State, although his name is unknown. There were traces of the face cream found in a well preserved bronze jar with a lid very tightly sealed. There were yellowish white bumps found inside the jar, weighing about 6 grams in total. These special types of bronze vessels that prevailed in contemporary tombs of early and mid-Spring and Autumn Period were speculated to be cosmetic containers.13

Conclusion

Cosmetics were a very important part of ancient Chinese culture, much like how cosmetics are important in today’s society. It is very interesting to learn about the different ways that women could find to apply a change to their skin to please society, even if that chemical ends up damaging their skin. Along with the history of ancient Chinese cosmetics, it is informative to find the scientific data to further improve the knowledge of these past cosmetics especially when there is residue to study. There is a large variety of cosmetics within China, in the past as well as today, but hopefully it is more appealing to the skin to last for many hours while protecting the skin.

Bibliography

Benn, Charles D. China’s Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford ; Oxford University Press, 2004.

Han, B., J. Chong, Z. Sun, X. Jiang, Q. Xiao, J. Zech, P. Roberts, H. Rao, and Y. Yang. “The Rise of the Cosmetic Industry in Ancient China: Insights from a 2700-Year-Old Face Cream.” Archaeometry 63, no. 5 (2021): 1042–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12659.

Schafer, Edward H. “The Early History of Lead Pigments and Cosmetics in China.” T’oung Pao 44, no. 4/5 (1956): 413–38.

Schafer, Edward H. The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics. San Francisco, UNITED STATES: Hauraki Publishing, 2014. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/muhlenberg/detail.action?docID=4809481.

Yu, Z. R., X. D. Wang, B. M. Su, and Y. Zhang. “First Evidence Of The Use Of Freshwater Pearls As A Cosmetic In Ancient China: Analysis Of White Makeup Powder From A Northern Song Dynasty Lv Tomb (Lantian, Shaanxi Province, China).” Archaeometry 59, no. 4 (2017): 762–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12268.

- Charles D. Benn, China’s Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty, 108 (Oxford ; Oxford University Press, 2004).

- Edward H. Schafer, “The Early History of Lead Pigments and Cosmetics in China,” T’oung Pao 44, no. 4/5 (1956): 413–38.

- Edward H. Schafer, The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics (San Francisco, UNITED STATES: Hauraki Publishing, 2014): 276-83, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/muhlenberg/detail.action?docID=4809481.

- Schafer, “The Early History of Lead Pigments and Cosmetics in China.”

- Schafer, The Golden Peaches of Samarkand.

- Benn, China’s Golden Age., 107

- Z. R. Yu et al., “First Evidence Of The Use Of Freshwater Pearls As A Cosmetic In Ancient China: Analysis Of White Makeup Powder From A Northern Song Dynasty Lv Tomb (Lantian, Shaanxi Province, China),” Archaeometry 59, no. 4 (2017): 762–74, https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12268.

- Yu et al.

- Yu et al.

- Yu et al.

- Yu et al.

- B. Han et al., “The Rise of the Cosmetic Industry in Ancient China: Insights from a 2700-Year-Old Face Cream,” Archaeometry 63, no. 5 (2021): 1042–58, https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12659.

- Han et al.